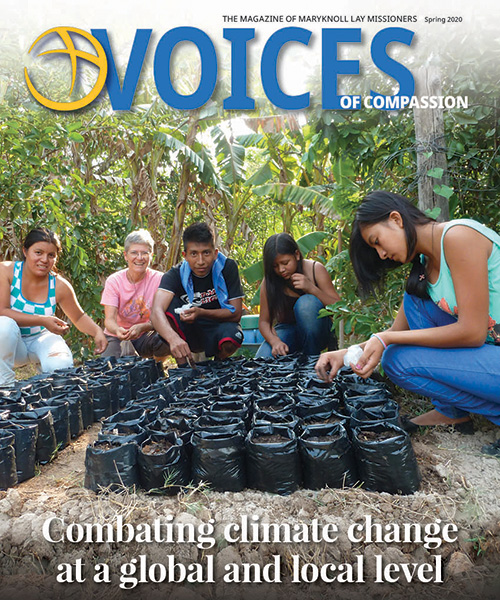

Peg Vámosy planting tree seeds with parish youth in Monte San Juan, El Salvador

It was only 3 in the afternoon when the sky turned so dark that Claire Stewart, a Maryknoll lay missioner in São Paulo, Brazil, thought she had lost track of time and night had fallen. Once she realized it was only mid-afternoon, she hurried home, assuming a sky that dark must mean a massive storm was brewing.

There was a storm of sorts, but not the kind she was expecting. Deep in the Amazon, a perfect storm of environmental issues came to the attention of the world through a series of fires in the rainforest that lasted from August through October. Smoke from the fires carried over a thousand miles from the Amazon to São Paulo, turning day into night and producing black rain.

A fire that was likely set illegally to clear a forest in Caparao’ National Park in Brazil’s state of Espirito Santo (Photo by Claire Stewart).

Photos from the Amazon that reached the U.S. during those months showed a sky on fire. That burning sky is a fitting symbol for the ecological crisis of our times.

Through their vantage point of living among vulnerable communities throughout the world, Maryknoll lay missioners like Claire often have front-row seats to the environmental disasters that are evidence of a planet in ecological distress.

Missioners serve as witnesses to the effects of these events on people in the communities where they live, and several lay missioners work in ministries that accompany those who are most affected, teach environmentally sustainable practices and raise awareness in the U.S.

Missioners in Latin America are particularly involved in a ministry of “caring for our common home,” as Pope Francis puts it in Laudato Si’, his encyclical on the environment.

In João Pessoa in northeastern Brazil, one of these lay missioners is Flávio Rocha da Silva, who promotes a spiritual awakening around environmental issues and advocates for a concrete response to destructive business and agricultural practices that harm the environment. Through his research, which he publishes in a variety of websites, blogs, and scientific magazines, he especially brings awareness of the connection between land issues and water.

Many of his articles are collected in an e-book that was just published in Portuguese in commemoration of World Water Day on March 22.

Flávio Rocha gives a presentation on the state of the São Francisco River at the Third Meeting of Ecology and Politics in Salvador de Bahia, Brazil.

Flávio explains that most of the fires in the Amazon were started deliberately—part of a trend of increasing deforestation, which is one of many human practices that are contributing to climate change. One problem with deforestation, according to Flávio’s research, is that “science has shown the great importance of forests for maintaining rain cycles—not only in the Amazon, but throughout the world.”

He goes on to say, “It is as simple as this: No forest, no water.” And he notes that water shortages are instrumental in causing mass population displacement, forcing “millions of people to migrate to big cities like Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo.”

Lay missioner Joanne Blaney, who works in São Paulo, concurs that the growth of the city is due in part to environmental factors. The city’s ever-growing population today exceeds 12 million. As she explains, “People left the rural areas because of droughts as well as lack of jobs and other economic opportunities,” with the result that 86 percent of Brazil’s population is now urban.

For most newcomers to São Paulo, however, dreams of financial success and freedom from environmental stresses turned out to be an illusion. Because the city’s population has grown faster than its infrastructure, 2 million of its people live in favelas—informal, resource-poor communities that lack many basic services such as trash collection, access to clean water, and sewage management.

Ironically, the same environmental factors that lead to drought and subsequent migration, are also creating increasingly torrential rains, along with other changing weather patterns. In fact, on Feb 10 this year, São Paulo was hit with what Joanne describes as “the worst flooding in 40 years, shutting down highways and side streets, stranding cars and trucks and buses.”

Joanne Blaney (left), with Maryknoll Sister Aremline Sidoine and José Silva, an educator and community leader, in the favela of Capão Redondo. which has high levels of urban violence and environmental degradation (caused by both drought and flooding)

While these conditions are difficult for the general population, Joanne says they are worst for “the estimated 35,000 homeless people living on the streets in São Paulo.” Glaucia, a local homeless woman, described her fear and hopelessness to Joanne in the aftermath of the rain. “I was so afraid,” she said. “The little that I have was ruined. . . . Many of us are sick, and I lost my medications in the chaos.”

Having witnessed people navigating these complex issues, Joanne agrees with the conclusions of the Synod on the Amazon that was held last October in Rome. The synod’s final document states that the displacement of people due to a mix of economic and environmental factors “demands a joint pastoral response in the urban slums” and “missionary teams” prepared to accompany the people who live in them.

One of the most visible environmental issues in urban centers like São Paulo is the accumulation of trash, which clogs gutters and storm drains, increasing the possibility of flooding during heavy rains.

Claire Stewart responds to this issue by seeing the potential for creativity and beauty in what others would consider garbage. In the art classes she teaches for children from low-income families, Claire uses recyclable items from the trash, including “toilet paper rolls, water bottles, lids, egg cartons, yogurt, recycled paper, as well as plastic and Styrofoam packaging from the market.”

In addition, Claire’s classes focus on “ways we can reduce our carbon footprint, the importance of plants, and ways to save the bees.” Her approach seems to be a success. “Within each of the spaces I have taught,” Claire reports, “I have seen a significant increase in the use of recycled items in activities with the children outside of my class.”

Claire knows that her impact “is small compared to the 27,000 tons of trash that is produced by the city each day, but hopefully it is creating a sense of responsibility in how each of us affects the planet with the choices we make.”

Many of the environmental patterns in Brazil also affect other countries in Latin America. For example, more than 3,000 miles north of São Paulo, lay missioner Sami Scott reports that deforestation is also a problem for Haiti. Historically land was cleared for sugar plantations, she explains, and hardwood trees like mahogany, oak and red cedar were later cut down for export to pay off Haiti’s “debt” to France for its independence.

Today, Sami adds, “Clearcutting is routinely practiced for agriculture, and the cut trees are used for making charcoal, the country’s main cooking fuel.” As a result of these practices, now just a small percentage of the original forests of Haiti are left.

As with Brazil, these practices have led to soil erosion, shifting weather patterns, including drought and flooding, and migration to urban centers in Haiti and abroad.

Sami Scott holding the first eggs laid by the chickens in a new project at the Jean Marie Vincent Agricultural Center in Gros Morne, Haiti.

Sami lives about four hours north of Port-au-Prince in the small town of Gros-Morne, and she works at the nearby agricultural center in Grepin, which models sustainable agricultural practices and good water management for local farmers. Sami describes one of the many goals of the center as “showing people that you don’t have to cut down your trees to do agriculture successfully and make money.”

Using a variety of crops, including fruit trees, the center teaches farmers ways to both feed their own families and create commercial crops, without first clearing their land. The center’s reforestation program plants up to 60,000 trees each year.

Haiti is not alone in sharing many of the patterns that lay missioners witness in Brazil. In El Salvador, lay missioner https://mklm.org/profile-peg-vamosy/ is concerned that deforestation, chemical-dependent agriculture and the prevalence of uncollected trash are major problems.

She explains that “not long ago, people would have used a banana leaf to wrap things. When you were done, you just threw it on the ground and it rotted away.” Now that packaging uses non-biodegradable materials like plastic and worse, Styrofoam, trash accumulates in unsightly piles on land and contributes to water pollution.

Peg works to raise awareness of the need to recycle, but she believes the ultimate solution is to stop producing so much plastic and Styrofoam in the first place. She is convinced that “there is an enormous international packaging industry that has to retool itself.”

Peg’s ministries are part of the effort of her parish in Monte San Juan, El Salvador, to address environmental issues. Some of the initiatives Peg has led and participated in include educational sessions before Sunday Masses, reforestation campaigns, collection of empty pesticide containers, construction of recycling bins, and an effort to develop a watershed management plan for a nearby river.

In addition, Peg works with local farmers, promoting sustainable agriculture. Chemical fertilizers have been standard for most farmers, and many feared their families would go hungry if they risked trying to produce crops without them.

From left, Elena Alfaro, Sheila Girón and Margarita Hernández divide up yellow corn harvested in the organic field of the agricultural ministry of Monte San Juan Parish near Cojutepeque in El Salvador.

After seeing positive outcomes in the model field run by the parish group, however, some were convinced to try sustainable practices. They are now successfully providing for their families without chemicals that potentially pollute the ground and the water, and that can be harmful to their own health.

One of the most powerful aspects of this work for Peg is that it is true “community development—because nothing will change unless everyone is working together.”

In addition, she believes, “If local people see that they can have an impact when they work together, then environmental issues can become opportunities for people to be the drivers of their own future. Once they feel empowered, they can then work together to solve all sorts of problems, not just environmental ones.”

The similarity of the issues lay missioners witness throughout Latin America indicates that the fiery skies over Brazil last year were not an isolated incident but clues to a complex social and ecological puzzle.

As Pope Francis writes in Laudato Si’ (#139), the range of these issues, from deforestation to migration and overcrowded cities, suggests that “we are faced not with two separate crises, one environmental and the other social, but rather with one complex crisis, which is both social and environmental. Strategies for a solution demand an integrated approach to combating poverty, restoring dignity to the excluded, and at the same time protecting nature.”

As lay missioners around the world know, many of the patterns seen in Latin America are echoed in places as distant from the Amazon as Cambodia or the informal settlement of Kibera in Nairobi, Kenya.

The global nature of these issues has convinced Marj Humphrey, director of missions for Maryknoll Lay Missioners, that responding to them is an urgent priority and a moral imperative.

“As missioners, we have felt the devastating impact of climate change and pollution on our world’s most vulnerable people,” Marj says. “Though we have several lay missioners who are involved in these issues worldwide, we continue to look for new and better ways we can respond. In conscience, we cannot do otherwise.”

All photos courtesy of lay missioners.

You can find an archive of previous issues of Voices of Compassion magazine here.

Great Article, Vicki!