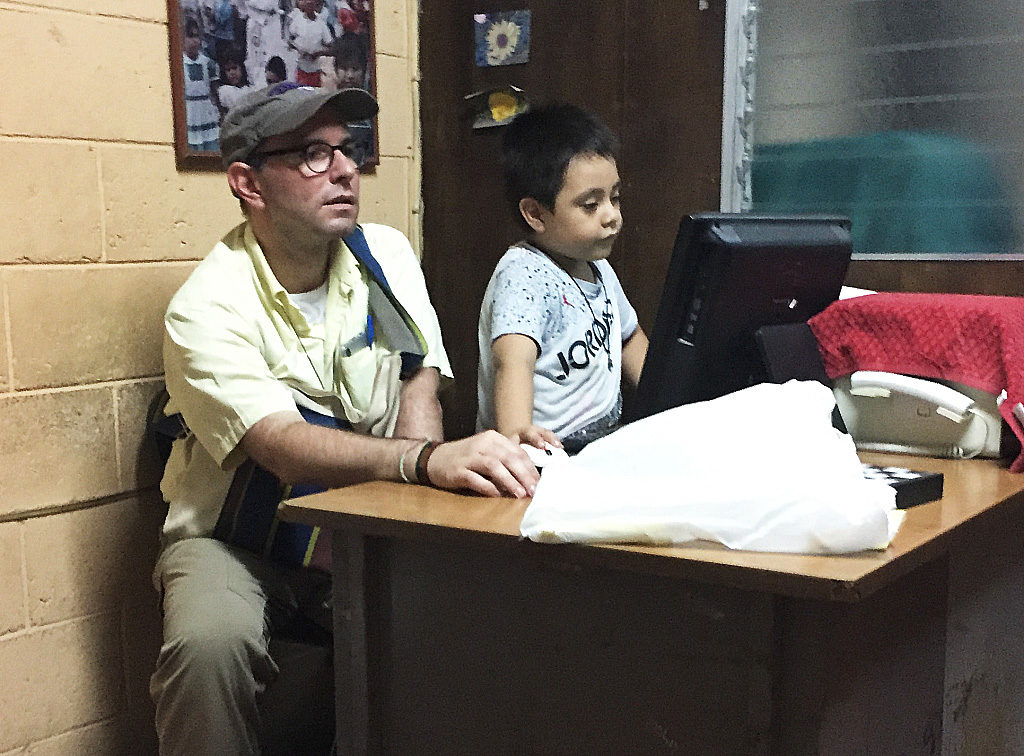

Pre-quarantine, Maryknoll lay missioner Joe Miller (back row, with cap) with Generación Romero in San Salvador.

On March 11, El Salvador implemented a mandatory quarantine for 30 days upon foreigners entering the country. The following week, all commercial centers were ordered closed; as were maquilas (“sweatshops”) and call centers (customer service contractors), leaving more than 100,000 people immediately out of work.

Then, on March 21, following the confirmation of the first positive coronavirus cases, El Salvador implemented a national quarantine for 30 days. The mayor’s office in San Salvador has begun work to establish 118 tombs in the cemetery for any deaths.

As of today, March 27, El Salvador has 19 confirmed cases of COVID-19, with at least 2,000 persons in quarantine centers. A “State of Exception” has been approved, giving the executive powers to suspend constitutional rights. It is a move that in principle I agree with, but, in light of his recent action involving the military and the legislature, is at the same time alarming.

One of the eight “core values” of Maryknoll Lay Missioners is “Building Bridges with the U.S. Church”—encouraging, indeed calling, missioners to share our experiences with the church in the U.S. But certainly mission is a two-way street. Often those of us from the U.S. walk into mission with the idea that we will serve, and are then shocked/surprised/uncomfortable/even guilty when we realize we are gaining so much more than we are giving. What could we give to each other in this time of universal Lent—both “universal” and “Lenten” in so many ways?

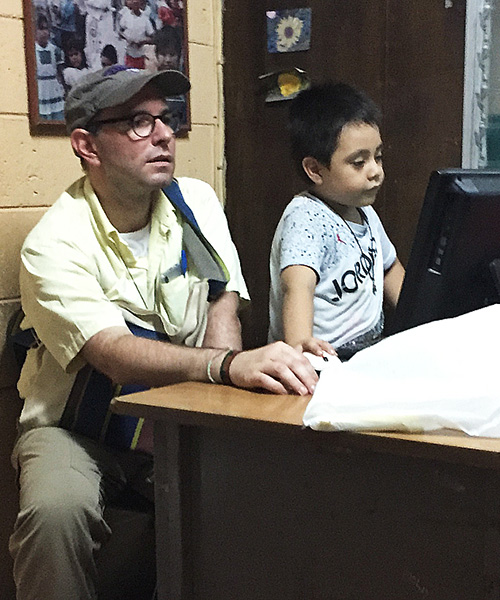

Alejandro, the “office manager,” a.k.a. “ray of sunshine” at Maria Madre de Los Pobres Parish, shows Joe how to work the computer (read: play video games).

The current global health crisis with COVID-19…. Well, let me back up: There was a global health crisis going on before this; it’s just that now those who are typically shielded from catastrophe and the unknown have had catastrophe thrust (or coughed and sneezed) upon them.

In places like El Salvador, the precariousness now visiting people in the U.S. has already been present everyday. Get bitten here by the wrong mosquito, you contract Dengue fever, Chikungunya, or Zika (remember that one?). Give the CDC’s COVID server a break and check out those pages instead!

Eat the wrong food, or drink spare water from old agua cristal jugs sitting next to the shower, and you can contract dysentery—still a thing, and yes, I do know from experience!

Might there be a chance in all of this to also reflect on global inequity—especially in healthcare—and how much of a crapshoot that makes life in an area (like here in El Salvador) where people don’t have access to clean, regular running water and are now told to wash their hands frequently? That is “normal” for many countries in the global South.

When people in the U.S. ask about when will things return to “normal,” are we sure that “normal” is the place to which we want to—or should—return; at least completely?

Perhaps the flipside of the uncertainty and catastrophe staring down the U.S. now is that there is in countries like El Salvador a certain gift of time. Because this virus spread faster in the U.S. and Europe, Latin American and African countries have been able to see and study those patterns, and at least some have enacted measures accordingly. Often disasters just happen here, and because so many live “on the edge” in poverty, they’re pushed over the edge because there’s no time to prepare, or no money to buy what’s needed to do so.

Maybe this virus is a chance to re-evaluate the ways we live that rob poor people in places like El Salvador of the care they need—or, indeed, of a basic, dignified human existence. Maybe this is a chance to finally realize how connected we are—and act on it—instead of just spouting more platitudes about “uniting together to overcome this.”

Now that we’re suffering in ways we usually think to be far away from us, I’d argue we don’t have a choice. And I suggest we look at the example of Jesus—who didn’t make any excuses, or justify inaction with laws when caring for the sick and outcast.

I’m writing this on the simple back patio of my host’s home where I expect to be spending a lot of time in the coming weeks during our 30-day absolute quarantine. No one is to leave their houses for a month, with exceptions for workers deemed essential.

There is also an exception for buying groceries—which I’ve learned means one person per household on two days a week—an ID must be carried, as well as a receipt from the purchase, and even a utility bill to prove to police and military checkpoints that you live nearby.

Unlike most shelter-in-place orders in the U.S., there is no allowance (at least at this time) for going outside to exercise while maintaining distance from others. Has that stopped some of us from going out within our residencial (gated neighborhood; they all are) to “get tortillas” from the woman down the street (read: walk around the block)? I hate to admit it, but what would you do after being cooped up for a week?

I wasn’t happy when the national quarantine was announced (though I knew some kind of restriction was coming). I felt like my freedom was being taken away (and of course it is), and it is hard to experience this in a foreign country—one where I was just beginning to find friends, explore work, and settle into a more regular routine.

But I do hope that, because this government started taking these precautions with three confirmed cases, El Salvador’s curve may turn sharply to the right and flatten in comparison to the U.S. Right now, this is what “uniting together” means here—giving up our personal freedom to give ourselves the collective best shot we can have to keep infected cases manageable.

To date (March 27), no Salvadorans have died from COVID-19 within the nation’s borders. One did die in New York City, and so gets counted in that city’s grim tally.

All of us Maryknoll lay missioners here in El Salvador were given the option to return to the U.S. I declined for the time being. One strange reality is that I currently feel safer here in El Salvador than in the U.S.

If I had gone home, there was a good chance I would not be able to return to El Salvador for many months. And that is the main reason why I will stay as long as I can. Transitioning into and out of mission life is difficult. If I was to leave now, I doubt I could successfully transition back into life here.

In the meantime, please pray for the safety of all of our missioners worldwide, and take care not only of yourselves, but all of your family and friends by staying away from each other. Go out to get food and pharmaceuticals, go out for walks around the block/farm, but other than that, stay home!

Thank you so much for sharing Joe. Please take care of yourself.

Sonny