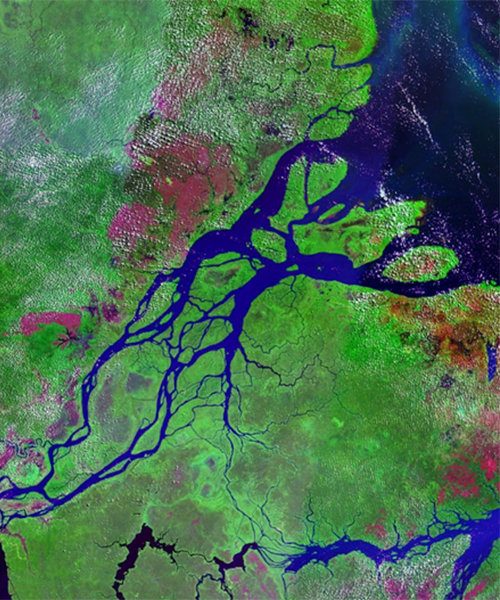

Aerial view of Amazon rain forest (Wikimedia Commons)

Water is often viewed in isolation from land. This separation is a result of a mentality that sees things as disconnected. But science has shown the great importance of forests for maintaining rain cycles—not only in the Amazon region, but throughout the Earth. If the forest is gone, it will affect the water cycle and a whole ecosystem of rivers and lakes in a region.

Some 20 percent of all the water in the ocean that comes from rivers originates in the Amazon river. As water has become a huge issue on the whole planet, who in their right mind would think that destroying the Amazon is a good idea?

It is as simple as this: No forest, no water.

Scientists have also shown that human presence, through the migration of ancient indigenous people, was very important for developing biodiversity in the Amazon forest. The problem is not having humans living in the forest, but how and why they live there.

Most of the Amazon forest is located in Brazil, and some of it is being deforested by multinational corporations from Canada, Europe, Japan and the United States, either directly or indirectly. Some of those lumber companies outsource this job to small and large local Brazilian companies, so their names do not appear if there is an investigation or the media denounces the illegal logging in that area.

Many communities have been affected by the lumber activity because many people make their living by extracting rubber from the rubber trees. But without trees, there are no jobs for those families and they end up migrating to big cities to live in shanty towns. Overexploitation of natural resources forces local people to leave behind not only their land but also their traditional ways of living in the forest, which were developed over generations.

Another huge threat to the Amazon region is the presence of mining companies. Multinationals have been exploiting minerals, especially in the state of Pará, and have caused damage to different communities by polluting their rivers and their lands. The chemicals tossed into the rivers would take decades to dissolve, even if there were a clean-up now, which is not the case.

Big dams such as the Belo Monte Dam have also made an intervention in the river´s natural course, while evicting thousands of people from their homes. Many of those families have only church groups to advocate for them. One of the results of those dams is that some fish species are in risk of extinction because some of them only exist in that ecosystem.

Soybeans are another element that plays a big role in the deforestation. Ironically, soy is not part of the Brazilian diet. Almost all of its production is exported to North America and Europe to feed animals. The same is happening in the Cerrado, the Brazilian savanna, an extremely important ecosystem where crucial Brazilian rivers like the Tocantins and the São Francisco rivers start. Again we see the connection between land and water.

The Amazon Synod, which will take place from Oct. 6 to 27 in Rome, will be a good moment to highlight the Amazon region’s many problems, including the current fires there.

Satellite image of the mouts of the Amazon river (Wikimedia Commons)

It will also be an opportunity to show to the world why people like Chico Mendes and Sister Dorothy Stang were in love with the Amazon and its people. It is such a sacred place with so many diverse species and indigenous groups that for that alone, it is worth preserving it.

With their limited knowledge, politicians who have the power to make decisions often do not understand the sacred nature of the Amazon and our duty to preserve it. On the other hand, some environmentalists advocate for a complete isolation of the forest with no human presence, which is another mistake.

What is necessary is not for the Amazon to become a sanctuary which no people will approach. We must understand the way in which Amazon communities—the people of the forest and the water—live and promote that way while offering them what science can offer without any imposition.

People across the globe especially in the northern hemisphere have many ways in which they can help preserve the forest in the South. One would be to make sure that companies that have their headquarters there and do business in the Amazon are acting with respect to that ecosystem and the communities who live in that region. Another is participating in their parishes and faith-sharing groups to reflect on how they can be connected with the Amazon Synod in a way that will strengthen solutions at this very crucial moment for our planet.

Science shows the interconnectedness of the ecosystems in our planet. To destroy the Amazon forest will inevitably affect the water cycle in ecosystems in other parts of the Earth.

The ecological conversion that is required today, Pope Francis writes in his encyclical letter Laudato Si´, “also entails a loving awareness that we are not disconnected from the rest of creatures, but joined in a splendid universal communion. As believers, we do not look at the world from without but from within, conscious of the bonds with which the Father has linked us to all beings.”