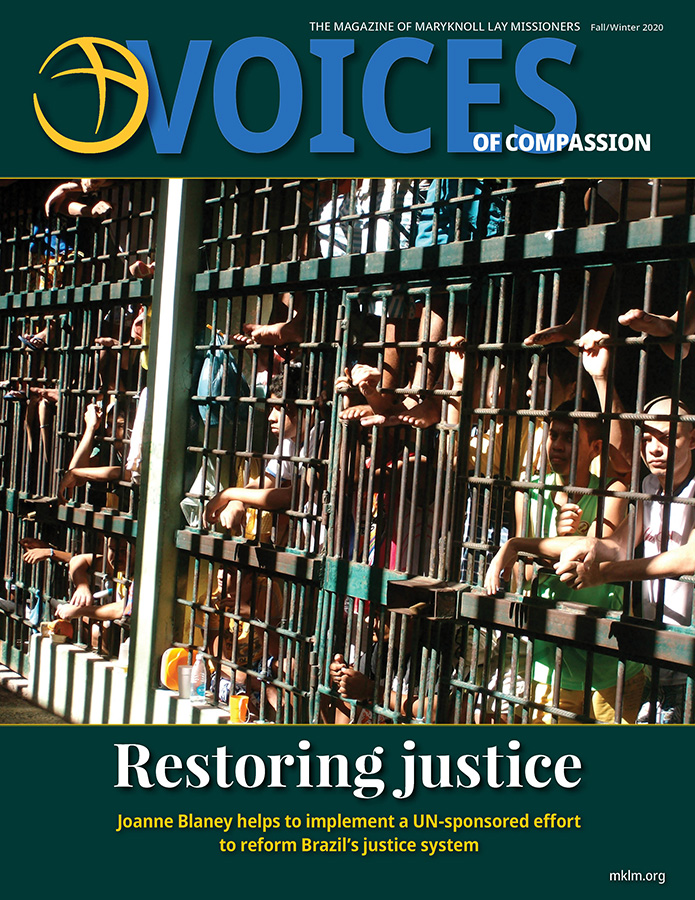

Prison in the state of Bahia (Photo courtesy of Prison Pastoral Ministry of Brazil)

Mass incarceration. Racial inequality. Excessive use of force by police. To anyone who has followed the news in the U.S. over the past year, these complaints will feel all too familiar. But according to Maryknoll lay missioner Joanne Blaney, these complaints are also frequently heard in Brazil, where she is inspired by the countless people and organizations working to reform what many refer to as the “injustice system.”

Currently more than 750,000 people are in prison in Brazil — and more than 35 percent of them have not even officially been sentenced yet. The high numbers are, in part, the result of a heavy emphasis on “law and order” coming from Brazil’s President Jair Bolsonaro. Brazil now has the third highest incarceration rate in the world — behind only China and the U.S.

Training Brazil’s courts in restorative justice

Joanne at the Center for Human Rights and Popular Education (CDHEP) in 2008 (Photo: Sean Sprague)

The good news is that Brazil has begun taking steps to address these seemingly intractable problems through a new program jointly sponsored by the United Nations Development Fund and three Brazilian organizations. The new initiative, called the “Restorative Justice Nework,” is offering training in a new paradigm and approach to crime: restorative justice.

The group chosen to implement the program is the Human Rights and Popular Education Center (or CDHEP), which is based in São Paulo and will celebrate its 40th anniversary next year. Since the 2000s, CDHEP has also been involved in restorative justice practices.

Blaney, who has lived in Brazil for 20 of the last 23 years, joined the staff full-time in 2008. She has taught restorative justice practices in prisons throughout Brazil as part of her pastoral ministry and also helps individuals and groups use those practices to address conflict.

Now she and the other members of the CDHEP team are also spending their time implementing the new UN-sponsored project through an 18-month course that provides training, accompaniment and supervision in using restorative justice practices. Current participants come from 10 state tribunals (state supreme courts) throughout Brazil.

The course was originally planned to take place in person, but because of COVID-19, much of it has moved online.

For each tribunal, the course participants include judges, state judicial workers, and representatives of the community. The ultimate goal is for each tribunal to create a network of people trained in restorative justice and to establish a local center for restorative justice able to train others in these practices.

Starting with the victim

Blaney explains that one of the biggest differences between restorative justice and the penal justice system with which most of us are more familiar is that the latter is concerned primarily with the offender and has the goal of assigning punishment for the crime. Restorative justice, on the other hand, “begins with a focus on the pain and grief of the victim, who, in sharing, begins a healing process.”

That sharing is done through various processes and dialogues that include not only the victim and offender, but often also their families, social networks and representatives of the broader community. Blaney defines a successful process as one in which “the traumatized victim can move forward in life, and the offender, after assuming responsibility and repairing the harm, can also reintegrate back into society.”

Mariza (left; not her real name), who lost her son to violence, with Joanne. Mariza has participated in a restorative justice process led by CDHEP. Today she helps mothers whose sons have been killed or who are in prison. (Photo courtesy of Joanne Blaney)

This community-based approach reframes crime, violence and conflict not merely as interpersonal interactions affecting two parties, but as a disruption and injury to the community as a whole.

As a facilitator of these processes over many years, Blaney has been impressed with the transformation that often takes place in them. Through dialogue, the victim develops a new narrative in which the offender is no longer a “monster” but “becomes humanized.” Blaney adds that for both the victim and the offender, “a well-run restorative process helps people get in touch on a deep connective level, to the place where compassion is born.”

Mariza (names of all program participants have been changed), for example, was devastated when her 20-year-old son was killed in front of her home. Presenting herself at the police department every day to ask about her son’s case, she found the police dismissive. They implied that her son would not have been killed if he himself had not been involved in criminal activity.

Mariza eventually turned to CDHEP for help, and was able to share her pain. Blaney recalls that as the restorative process unfolded, Rodrigo, the young man who had killed her son, began to understand the full impact of his act. He also offered Mariza the comfort of knowing that she had been right: Her son, Paulo, had not done anything wrong.

As a “motoboy” (picking up and delivering documents from businesses and individuals), Paulo had worked in a stressful and dangerous job in São Paulo, weaving through gridlocked traffic to meet rigid delivery deadlines. Rodrigo had just been robbed by someone on a motorcycle and attacked Paulo, mistaking him for the thief.

Meeting Mariza face to face, Rodrigo accepted responsibility for his crime and begged for forgiveness. “In that moment,” Mariza says, “I saw another young man just like my son and was able to forgive.”

This encounter changed both Mariza and Rodrigo’s lives. As part of his restitution, Rodrigo now tells his story to other at-risk youth. Mariza works with children and helps mothers whose sons have been killed or who are in prison.

From grief and rage to forgiveness

Joanne outside the Women’s Penitentiary Sant’Ana in São Paulo, where she has done restorative justice work with women prisoners for many years

Again and again, Blaney has experienced this level of extraordinary transformation from grief and rage to forgiveness and a new sense of purpose. As she puts it, restorative practices use “storytelling to break isolation and demonizing, and to build empathy that leads to a sense of community.”

The fact that both Rodrigo and Mariza are involved in addressing ongoing issues of violence in the community is an important aspect of the work. For Blaney, violence is often “like an iceberg” and the penal system deals “only with the tip of the iceberg — the relational violence between people and groups.”

In restorative justice, she reports, “The idea is to see that many individual conflicts also have to do with structures that are unjust — not to remove individual responsibility but to recognize that there is also a collective responsibility. Violence (whether psychological or physical) many times is a scream for justice.” CDHEP therefore includes analysis of levels of structural violence in their trainings.

In another case, Thiago, an adolescent who hijacked a car, agreed to a restorative justice process while on probation. The process included the victim, her family, representatives of the school, social service workers and other members of the community.

During the dialogue, it was revealed that Thiago’s mother, who was struggling with mental illness, would often disappear for days or even weeks at a time. Thiago had turned to stealing to feed and clothe himself and his siblings. The penal justice system punished him for his actions, but did nothing to address the conditions that led to the crime.

In cases like these, Blaney believes true justice must take account of the needs of both the victim and the offender—who may be trapped in circumstances that make returning to crime inevitable unless help and support are provided.

In restorative justice, Blaney says, “there are no ready-made answers and each process is different. At times we enter the process trembling yet believing that . . . the power of the Spirit will be at work.” Another challenge is that the process only works if all parties are willing to participate and the offender accepts responsibility for their actions.

Despite these challenges, there is growing evidence that restorative justice is more effective at reducing crime and violence than a system based on punishment. “Restorative processes,” a UN handbook states, “have a greater potential than the standard justice process operating alone to effectively resolve conflict, secure offender accountability and meet the needs of victims.”

More than 90 empirical research studies in seven countries have found positive impact of restorative justice dialogue in juvenile and criminal cases. According to one mega study, restorative justice processes reduced the recidivism rate by 55 percent for grave crimes as compared to the high recidivism rate in the penal system.

While Blaney and her colleagues at CDHEP have been training people in restorative justice for many years, this project raises these efforts to a national level. That is important because, as the UN points out, restorative justice processes can only become a viable alternative if they are integrated into the culture of a nation’s approach to and assumptions about justice.

The U.S. is a case in point. Some states, like Vermont and Minnesota, have been using restorative processes, especially in cases involving juvenile offenders, since the 1990s. But rules governing these processes vary by state, and on the whole, restorative practices have not been fully integrated into the national system. Therefore, even when restorative practices are available, the prevailing tendency is to resort to the more familiar patterns of a system focused on punishment.

‘Curing souls’

Incarcerated women in their prison cell in the state of Bahia (Photo courtesy of Prison Pastoral Ministry of Brazil)

Responses to courses offered by CDHEP have been overwhelmingly positive. One participant described learning about restorative practices as “a revolution, almost like the invention of light.” Another summed it up well: “This course cured my soul.”

Best of all, judges and other participants in the current, UN-sponsored program seem enthusiastic about incorporating restorative justice practices into their tribunals in the future. “This course brought us hope that there is another model [of justice] that is humane and more effective in dealing with violence and injustices,” one participant said.

Blaney, too, has been profoundly affected by the work CDHEP is doing. Accompanying people through their journey of recovery after a crime has deepened her understanding of the Paschal mystery of dying and rising. It has taught her that “out of pain and suffering can come hope … [and] a liberating process for all, where the fire of the Spirit heals and frees up energies for the building of God’s reign.”

Blaney also sees these processes as getting to the heart of “what mission is: accompanying people but not doing for them or to them. The collective energy of these processes brings out an inner wisdom that can heal people and build a community spirit that can bring more justice and peace to our communities.”

Perhaps her experience points to what mission is in another way too. In an increasingly interconnected world, missioners offer their skills and talents in the communities where they are placed. But they also learn from the people and cultures they live among, and they bring those stories back to the U.S.

There is no question that, like Brazil, the U.S. yearns for a different future for its police, court, and prison systems. Perhaps the vision of justice being lifted up in Brazil can provide a model for the U.S. as it strives to live up to the promise of being a nation that offers liberty and justice to all.

This article is the cover story of the Fall/Winter 2020 issue of Voices of Compassion, the magazine of Maryknoll Lay Missioners.

To read a PDF copy of the magazine, click here.

You can find an archive of previous issues of Voices of Compassion magazine here.

.