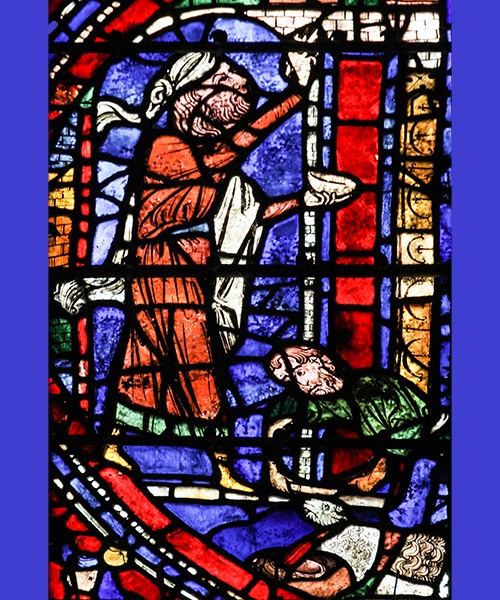

Slaying the Passover lamb, Chartres Cathedral (Photo by Fr. Lawrence Lew, OP, via Flickr)

This morning on NPR, a show host asked a rabbi why God would allow something like COVID-19 to exist. How can a loving God let so many people get sick and die?

The question is understandable especially at this moment when both Christians and Jews are celebrating some of their holiest days of the year. Passover began on the evening of April 8 and goes through April 16. Holy Week began last week and gives way to Easter week this week. The sacred stories behind both those holidays lead us to expect something celebratory this week—a new freedom, and ultimately for Christians, freedom from death itself.

But for many of us, this is not an unqualified time of celebration. Many are in mourning for those lost to the coronavirus. Many are still fearful that those we love could become sick with the virus, that we ourselves could fall ill, or perhaps worst of all, that we could be the source of infection that leads to someone else being exposed or even dying.

That dissonance between our religious hopes and our current world reality leads to the question the NPR host asked. There is something deep in the human psyche that equates suffering with abandonment by God. Even for those of us who never consciously had a belief that there was an all-powerful being who could rescue us from every evil, somewhere in the back of our animal brains, the equation persists: suffering and evil are incompatible with our vision of a good, loving, all powerful deity. Even Jesus seems to have felt that incompatibility, uttering from the cross what is perhaps the most heartbreaking line in Christian scripture: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”

The rabbi on the radio didn’t have a good answer to the host’s question. I don’t have one either. But I do think that, despite our expectations of celebration this week, it is powerful—and ultimately fitting—that some of the worst days of the pandemic are happening in the midst of Passover and Easter celebrations. Why? Because for both Jews and Christians, the message of these holidays actually resists our instinct that suffering means the absence of God.

Both traditions proclaim that God is here—and here in unique and especially profound ways—in the midst of suffering and death.

The metaphor behind the Passover especially interests me at this time. For Jews, Passover is about coming out of Egypt. But in Hebrew, the word for Egypt is “Mitzrayim” which at its root means “narrow place.” And isn’t that how we feel these days? Confined, constricted, needing to stay in our small spaces, our closed houses?

In the story, it is when the Israelites call out from that narrow place that God hears us and responds. The Israelites are often forgetful of their God, but they become most attuned to God’s presence when they are in the midst of that suffering. For the rest of history, their descendants will always link the two together: the memory of Mitzrayim, and the awareness of God’s presence.

Eventually, the Israelites come out of that narrow place through a door marked in blood and a journey through water. That, of course, is a metaphor for birth. That is how we all come into the world. We start in a cramped, but safe space, and we travel a dangerous passage through blood and water into the world.

In that metaphor, God takes on the role of mother; God is the one who “delivers” us. So while I don’t have an answer to the question posed on NPR, I do have a sacred story that tells me that our suffering does not mean we are forsaken. Even in the narrowness of our mourning and our fear, God is the mothering presence who is always in the process of delivering us into new life.

Vicki thank you. Beautiful reflection. New insights. Words of hope. This is labor pains working hard to birth us into new life!