The altar in the Divine Providence Hospital chapel in San Salvador. This is where St. Óscar Romero was assassinated on March 24, 1980. The inscription on the wall says, “At this altar, Archbishop Óscar A. Romero offered his life to God for his people.” The protective glass around the altar encloses and marks the spot where he fell to the floor.

On Monday, March 24, 1980, a red Volkswagen sedan pulled up in front of the chapel of the Divine Providence Hospital in San Salvador. In the backseat, a sharp shooter opened the window and fired a 22-caliber bullet that killed Archbishop Óscar Arnulfo Romero as he was celebrating Mass.

The Hospital of the Divine Providence, run by the Carmelite Sisters, cares for indigent people dying of cancer. It was also Romero’s home. When he became archbishop of San Salvador in February 1977, he took up residence here in a humble room behind the chapel. He wanted to be close to the suffering, and he often spent his evenings visiting patients.

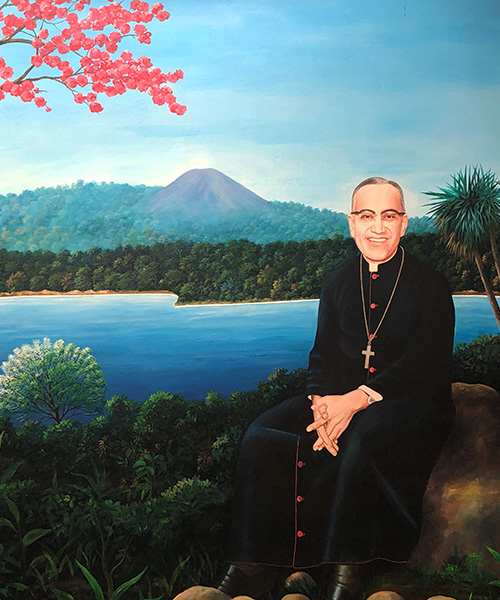

Maryknoll lay missioner Peter Altman stops at a mural to martyred St. Óscar Romero on the grounds of Divine Providence Hospital, near the chapel where the archbishop was slain 40 years ago in San Salvador.

The sisters later built him a small house on hospital grounds, which he didn’t ask for. The sisters knew he would be reluctant to accept it, perhaps even refuse it, so they gave the keys to a patient, a man whom Romero had become good friends with. The plan called for Romero’s friend to give him the keys to the new house. Romero couldn’t say no to him, or so the sisters thought.

They were right, and I often imagine Romero’s concerned face when the sick man put the keys into his hand. It turned out he humbly and graciously accepted the gift. Today the home is a living monument to Romero’s humility and proximity to the poor, even his tan Toyota sedan is kept here.

But how did a cleric, who became archbishop and had spent seven years (1967-1974) as secretary of El Salvador’s bishops’ conference—where his proximity to suffering, repression and political persecution was perhaps more abstract than concrete—end up in a simple home next to the dying and indigent?

Part of the answer is found in the Diocese of Santiago de María, where Romero, after his years in the bishops’ conference, became bishop in December 1974.

The diocese wasn’t distinct from the rest of the country in which grave injustices and grave human rights violations were a part of the people’s lives. Seventy percent of the inhabitants in the diocese were hired hands and worked on coffee plantations or haciendas. There was a 40-percent illiteracy rate and a flagrant lack of schools. Children suffered from malnutrition and healthcare was nearly non-existent.

“In Santiago de María, I discovered misery again: children that die because of the water they drink and workers dying a slow death in the sugar cane harvests,” said Romero about his time in the diocese. Here he saw reality with his own eyes, touched it with his own hands, and heard it with his own ears.

In Santiago de María, Romero also began to question his neo-scholastic theological training and opened up to a dialogue with liberation theology and became a proponent of the church’s need for a preferential option for the poor. “I am a shepherd who, with his people, has begun to learn the beautiful and difficult truth that our Christian faith requires that we immerse ourselves in this world. The world that the church must serve is the world of the poor, and the poor are the ones who decide what it means for the church to really live in the world” (February 2, 1980).

Fifty days after saying these words, Romero was assassinated. His life and advocacy for justice and human rights, for being a voice of the voiceless, became a threat to the oligarchy and military dictators of the country. They dubbed him the “communist bishop.” To this day, many in El Salvador, even after Romero’s canonization, still think this way, but his legacy continues to grow and change many others.

As a Maryknoll lay missioner, I see Romero’s legacy as paramount to our ministries—to see with our own eyes, touch with our own hands, hear with our own ears. Reconciliation, relocation, and redistribution (in the spirit of Romero) is what we strive for—to provoke questions among ourselves and questions that build bridges with the church in the United States. “What gives me the right to live a better life than the people here?” asked one 18-year -old youth from Illinois during one of Maryknoll Lay Missioners’ Friends Across Border trips.

Josefina (left) with her sister, Nelly, preparing tortillas. Her 4-year-old daughter holds one of the children’s books from the community library.

I also see people like Josefina, who was abandoned by her husband. She is from La Esperanza and makes tortillas to support her 4-year-old daughter, her two brothers, sister and elderly grandmother. Her own mother died of an infection no antibiotic could stop, and her father died of kidney failure. Bad water, poor diet, agricultural chemicals are all contributing factors to this widespread ailment.

But Josefina doesn’t want my pity. She is a tough woman with a deep faith. That is sufficient enough for her. Yet she beams with a beautiful smile when I tell her that many of the books she reads with her daughter (from our library) come from “El Otro Lado” (The Other Side is what people here often call the United States; they say it casually, as if it were the mud hut just next door).

“Tell them I say gracias,” Josefina says. “Could they ever believe what joy it gives my child and me to read a few minutes at night together?” I tell her I think so, as she slaps the lumps out of a fresh tortilla and places it on a hot, steel plate. A dozen other tortillas are sizzling, turning goldish-brown. I sit down on a rustic wooden bench and wait for my order—I buy tortillas from her most every day. “Redistribution?” I ask myself.

It is one of my favorite moments of the day, not only for being close to Josefina (relocation?), but because next to her stove I’ve thought a lot about San Óscar Romero. I think of his faith and how it had nothing to do with ideologies or partisan politics. To the contrary, this small, insignificant place called El Salvador—as far as worldly power goes—became his Nazareth. It was his home, and he rediscovered it again and again through his passion and love for Jesus.

That gives me courage and hope.

Photos by Meinrad Scherer-Emunds and Rick Dixon