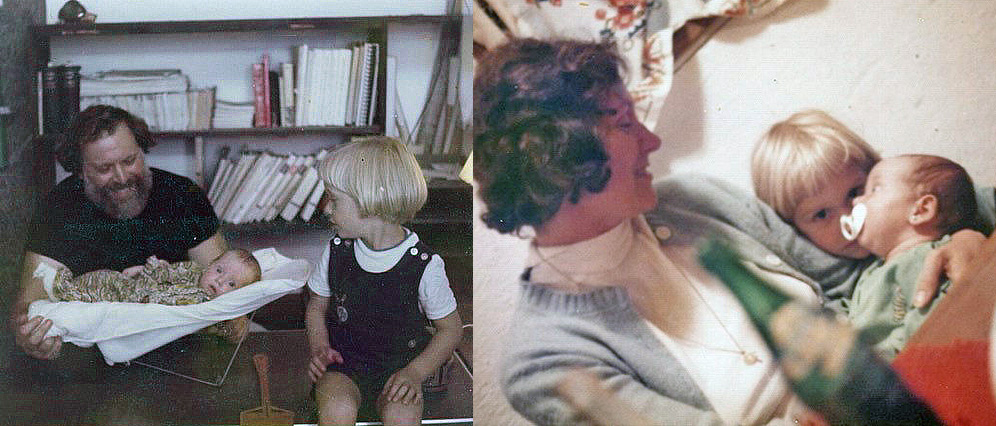

The Gauker family in Guatemala in 1976. Left: Lay missioner John Gauker with newborn daughter, Moni, and 3-year-old Johnny. Right: Phyllis Gauker with Johnny and Moni after Moni’s baptism. (All photos courtesy of Phyllis Gauker.)

In February 1976, a powerful earthquake struck Guatemala, destroying more than 250,000 houses and leaving 23,000 people dead and about 1.2 million people homeless.

In Auburn, Alabama, John Gauker and his wife, Phyllis, wanted to help. John owned a construction company and felt a call to go to Guatemala to help with the reconstruction. He and Phyllis kept coming back to Jesus’ command in Mt 19:21, “Go, sell what you have and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven. Then come, follow me.”

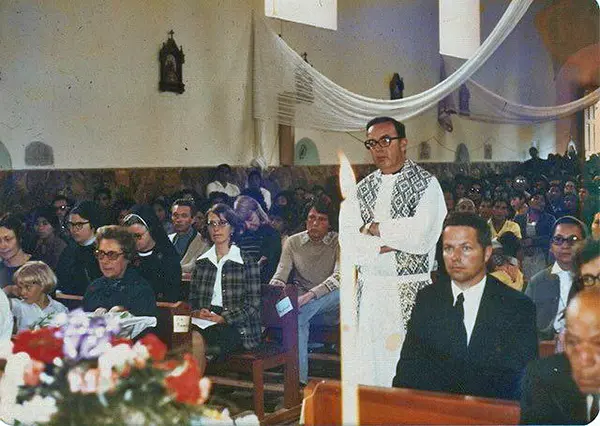

John and Phyllis Gauker with Father Bill (right) and godmother Marta Woods (Bill’s sister-in-law, front) holding Moni after her baptism on Oct. 15.

They knew some Spanish from having lived in Spain for three years, but John said: “We can’t just go to Guatemala and announce, ‘I’m here to help.’” Also, Phyllis was two months pregnant, and they had a 2 1/2 year old son, Johnny. So they weren’t sure if they should really pursue it.

About a month later, at a St. Patrick’s Day party at their parish, they talked to a retired engineer, who had served as a Peace Corps volunteer in Guatemala. He said he had worked with a priest pilot there who, if they wrote him that they wanted to help, would pray about it and then tell them, “Come on down.”

So that’s what they did, and Maryknoll Father Bill Woods did tell them to come down. Phyllis remembers, “He gave us no details, other than to pick up some stuff from his mother in Houston on our way (which we did). So we sold what we had, as in that scripture verse, and made a commitment to do this thing that we thought God wanted us to do.”

Father Bill told them that the plan was to build apartments for earthquake-displaced people on land he had purchased in Guatemala City for that purpose. He said he was waiting for the contractor to show up. Now John Gauker was going to be that contractor.

Phyllis says, “We did not know about the political unrest, or the danger in being associated with Father Bill, until after we arrived.”

For more than a decade, Father Bill had been involved in a land reform project in a remote jungle area called the Ixcán. The project had secured land for landless, indigenous Mayan campesinos and helped them to build homes and farms on that land.

Johnny with Father Bill in his plane

By 1976, about 2,000 Mayan families had been settled in five new towns, complete with schools and health clinics that had been carved into the Ixcán jungle.

But Guatemala’s military and land-owning elite now also had their eyes on this jungle area. The rise in oil prices in the 1970s was attracting foreign oil companies, which were aware of oil deposits there. The army was now increasingly active in the area, and in 1975 the army had begun kidnapping, disappearing and killing people associated with the land reform project.

When Father Bill sought out the military command, he was told to “mind my own business and preach the love of God to the people.”

In April 1976, the U.S. ambassador told Father Bill in a private meeting that the Guatemalan military were accusing him of collaborating with the guerrillas and that his life was in danger from top military brass — adding that the U.S. government couldn’t do anything about that.

Following the meeting, Father Bill sent a letter directly to Guatemala’s then-president, General Kjell Laugerud, stating, “I have never had any relationship with the guerrillas, and I have no political ideals.” He continued, “My only interest is to help make the peasants better Christians, better Guatemalans, and thus help them produce more for themselves and for their country.” He even extended to the president “a most sincere and cordial invitation to honor us with your visit to the Ixcán Project.”

After they arrived in Guatemala, Father Bill told the Gaukers about this threat to his life. “We really didn’t know what to do,” says Phyllis. “I think he was offering us a way out, as in, ‘If you want to leave now, I’ll understand.’ I remember John saying, ‘What will we do if that crazy priest gets himself killed?’ Little did we know.”

Phyllis says, “We really liked Bill as a person, and as a priest. … He had a real interest in the people and a curiosity about our interrelatedness on earth.” She and John thought and prayed about it. “We decided we were in for the long haul and would not abandon Bill.”

Inside the airplane hangar, where the Gauker family lived during their stay in Guatemala. For the first few weeks, they lived in the white storage room on the right, while an earthquake-displaced family occupied the hangar apartment.

The couple moved into an airplane hangar that Father Bill had leased. He had learned to fly in 1965 and used planes to transport people and supplies for the Ixcán project and bring the project’s harvested crops to market.

Everything seemed pretty normal, Phyllis remembers, except that one day, shortly after they had moved into the hangar, armed soldiers sped up to the place, jumped down from the truck and pointed their rifles at Phyllis and John. They were demanding roofing materials that Father Bill had brought with him from the U.S. They were going to be used in the Ixcán project, and the army confiscated them so they could be the ones getting the credit for handing them out.

Father Bill would sometimes say Mass in the hangar, and a few weeks after the Gaukers’ second child, Moni, was born in September, she was baptized during one of those Masses in the hangar.

The official Maryknoll lay mission program had been launched the previous year, in 1975, and Father Bill talked with the Gauker family about them at some point attending the lay missioner orientation and formation program in Ossining, but that did not happen.

Shortly after Moni’s birth, the Gaukers spent a week in the city of Teculután, where John was “lent” to Canadian priests to help with the rebuilding of a bridge.

Sometime after returning to the hangar, Father Bill invited the whole Gauker family to fly with him to the Ixcán to see the project there. They were to fly on Nov. 20, 1976.

“We had had a trying experience with Moni in Teculután,” remembers Phyllis. Because of the heat and humidity there, “she had cried the entire time … and only stopped crying when we returned to the altitude and relative coolness of the capital. Therefore I knew she could not tolerate the heat in the Ixcán, so I declined for me and the children. Even that morning, while Johnny was crying to go, Bill said he could take him because the plane was not full, but I emphatically said no and didn’t really know why I was so adamant about it.”

During the funeral Mass for those who died in the plane crash. At right, John Woods (Father Bill’s brother); standing next to him in the aisle, Maryknoll Father Ed Moore; and in the front row on the left side (from left): Phyllis, Johnny and Maryknoll Sister Cecilia “Nati” Ruggiero, who is holding Moni; behind her is Maryknoll Sister Mary Malherek.

Phyllis says she closed the door to the plane “while my son was still crying to go with his Daddy.” Besides Father Bill and John Gauker, two volunteers with the U.S.-based Direct Relief Foundation and a friend of the Gaukers, who was assigned to take photos of the Ixcán project for Maryknoll magazine, were on board as well.

Phyllis recalls:

That afternoon at sunset, I called on the ham radio in the hangar to Mayalán, asking for Bill. The answer was, “El padre no ha llegado” (The Father has not arrived). I knew then that the plane had crashed — no ifs, ands or buts about it. They were carrying a radio to be installed in one of the villages, so if they’d just been in trouble, they’d have radioed.

I took Johnny with me to the hangar next door, leaving Monica sleeping, and called [Maryknoll Father] Ron [Hennessey] to tell him what I knew. He … said, “Bill is forever landing in one place and forgetting to radio his arrival. It doesn’t necessarily mean anything.” But when I got back to the hangar, I heard him on the radio to Mayalán. When I’d radioed looking for Bill, they’d sent out a runner to the villages without radios in case he’d landed there first. Nothing. So now Ron began to worry, too.

Donna Whitson Brett and Edward T. Brett in their book Murdered in Central America: The Stories of Eleven U.S. Missionaries, write about what happened to the plane:

The Cessna, after weighing in to assure that it was not overloaded, took off at 10:01 a.m. Just as it cleared the last ridge through the canyon leading into the jungle, when the aircraft was only about 150 feet above the ridge, witnesses saw the plane begin to plummet towards the earth, then twist around and smash into the mountain it had just cleared.

A memorial Mass was said for John inside a hut at the housing construction site he had been overseeing. The Gaukers and Maryknollers celebrated the Mass together with the construction workers and their families. Front row (left to right): Maryknoll Brother Bob Butsch, a Canadian priest named Fr. Dave, Sr. Cecilia, Phyllis Gauker, Johnny, and Janie Holstegge.

According to his sister, Dorothea Woods Wedelich, Bill, while on vacation in Houston, had spoken to parochial school students in September and predicted that if the Guatemalan elite ever planned to kill him, they would plant soldiers on the last mountain ridge since his low-flying plane would be an easy target. As more questions than answers began to unfold concerning the crash, Bill’s prediction would assume [prophetic] significance.

Although witnesses testified that the weather was perfectly clear in the area that day, the Guatemalan army tried to blame bad weather for the crash. The military arrived at the site just a few hours after the crash, removed the bodies and tampered with the evidence. They did not inform Maryknoll or the families of the deceased until the following day.

Phyllis remembers a colonel from the Guatemalan army coming to the hangar to tell her the bad news: “The plane had been found and all were dead. As if in explanation for the cause of the crash, he showed me weather reports (which clearly showed clear skies!). Did he think I could not read?”

Today, within Catholic circles as well as among the Mayan Indians it is generally accepted that Father Bill, John Gauker and the three other passenger on that fateful flight were murdered by the Guatemalan generals. There have been reports of military officers who were overheard drunkenly boasting that they had killed Father Bill.

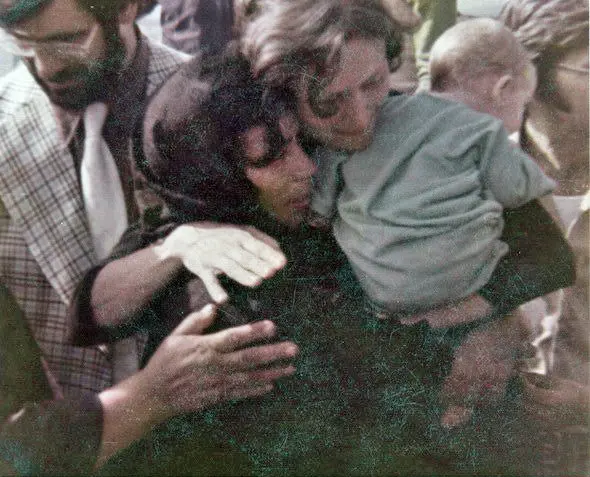

At the burial, Phyllis remembers, “a woman came out of the crowd and embraced me like a sister, whispering, ‘Soy viuda, tambien’ (I am also a widow). No further words were necessary because she understood my plight regardless of our differences.”

Father Bill’s and John’s names are the first in a long list of Catholic priests, religious, lay catechists, lay missioners and even a bishop who were assassinated and martyred in Guatemala between 1976 and 1998.

Not long after the crash, the Bretts write in Murdered in Central America, the Guatemalan army occupied the Ixcán settlements, a European oil conglomerate built roads through the area, and a highway was built to connect to Guatemalan President Lucas García’s newly acquired lands. The German missionary priest who served in the Ixcán after Father Bill was expelled from the country in 1979.

Then in March 1982, according to the Bretts, “over 300 people were murdered by the army at La Unión, one of Father Woods’s pueblos. Similar massacres were carried out by the military throughout the Ixcán project from March to June.”

According to the United Nations Historical Clarification Commission for Guatemala, more than 200,000 people were killed or disappeared in the decades-long Guatemalan civil war that ended in 1996.

In a letter she sent in 2006 to Thomas R. Melville, a former Maryknoll priest who wrote Through a Glass Darkly (a chronicle of atrocities in Guatemala and El Salvador, told through the story of Maryknoll Father Ronald Hennessey), Phyllis Gauker says, “I have such a heavy heart about this: rekindling of something I thought I had adequately buried…. If I ever attempted to tell it here in the States, I’d get such looks. It was all so unbelievable, and I had so little information.”

Phyllis Gauker today

Referring to her late husband, John, and to Father Bill Woods, she says, “I didn’t know if I should consider them martyrs or fools.”

Phyllis says that throughout her life, she has found consolation in scripture. She remembers that on Nov. 20, “After the plane taxied down the runway, I went into the hangar. I decided I should do my scripture reading right then because I might get too busy later to remember to do so. … Asking for some guidance for the day, I found some lines that did not make total sense at the time. But in retrospect, they made perfect sense. 2 Cor 6:2: ‘Today is the day of salvation.’”

Father Bill and John were both buried in the Maryknoll section of the cemetery in Huehuetenango, Guatemala. In 2000, at the request of the Ixcán people, Father Bill’s body was moved to Mayalán, Ixcán to rest in peace there.

Phyllis Gauker returned with her two children to Auburn, where she eventually remarried. She has taught choral music and for many years directed the Auburn Music Club Singers. “Music, specifically singing,” she says, “has been what held me together all my life — an outlet, a gift to be used for the right purposes.”

For more background on Father Bill Woods’s story, please see:

- Father Bill Woods, M.M., Martyr of the Ixcán. Video by Fr. David La Buda, M.M.

- The Bill Woods Story, by Donna Whitson Brett and Edward T. Brett

- A Cowboy for Jesus by Bishop John E. McCarthy (Maryknoll magazine, Nov 1984, pp. 58-62)

- The Strange Death of Bill Woods by Ron Chernow (Mother Jones magazine, May 1979, pp, 32-41)

- The Army ‘Brings Down’ Father Woods by Ricardo Falla (Chapter 2 from Massacres in the Jungle)

- A Warning and Then Some by Thomas Melville (Chapter 24 from Through a Glass Darkly)

Photo album

Click on the photos.

Deeds for farms

Fr. Bill passes out land deeds to Mayan farmers settling in new villages in the Ixcán (photo by Selwyn Puig, who also died in the 1976 plane crash).

Maryknoll priests at funeral

Maryknoll priests at the funeral, from right: Fathers Dan Lanza, Ron Hennessey and Frank Garvey.

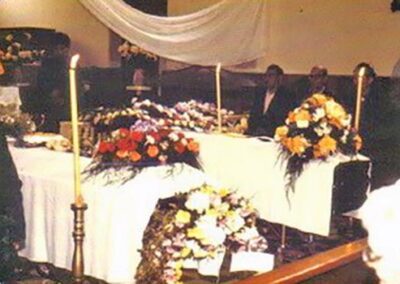

Caskets at funeral

The caskets of Father Bill Woods, MM, and John Gauker, at the Nov. 23 funeral Mass in Guatemala City.

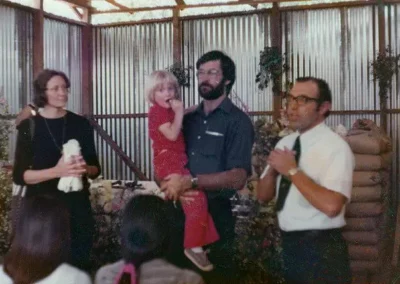

After Mass

Phyllis Gauker, Father Dave (holding Johnny) and Maryknoll Brother Bob Butsch address the assembled construction workers after the memorial Mass for John.

Sincere gratitude for this very powerful story.

Beautiful. A reminder to be brave in our darkness. Light will find us.

I don’t remember ever hearing about these brave souls

who took Jesus’ invitation to follow Him literally and whose

lives were sacrificed in the name of social justice. Now I

think I will never forget them. Thank you for sharing this

story of hope in the midst of darkness. It is truly a message

for our current times.

This story is rich and amazing. A story long overdue. I hope it remains posted for the remainder of Lent.

This is an amazing tribute to the Gauker family. The history of going where we feel we are being led with our brothers and sisters on the margin is rich and inspiring. Thanks for sharing.